The case for Planet Nine is growing. Two new findings presented at a planetary science meeting in Pasadena, Calif., have uncovered hints for the existence of this distant, mysterious world in the motions of known solar system objects.

The results could help astronomers home in on their target, which — if it really is out there — could fundamentally alter our understanding of the solar system.

The hunt for Planet Nine began in earnest in 2014 after astronomers Scott Sheppard and Chadwick Trujillo found 2012 VP113, a planetoid nicknamed "Biden." Its closest point to the sun in its orbit is 80 astronomical units — that is, 80 times the Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles.

Objects like 2012 VP113 exist far beyond the typical denizens of the Kuiper belt, the icy ring of debris that stretches from Neptune's orbit at 30 AU out to 50 AU (and whose largest member is distant Pluto, sitting around 49 AU).

The scientists also noticed that 2012 VP113 and another far-out mini-world named Sedna were making their closest approaches to the sun at similar angles — which could mean that something massive but unseen was tugging on both their orbits. Since the scientists could not directly see a planet in the darkness of our solar system, they would have to keep searching for its gravitational fingerprint on the motions of other bodies.

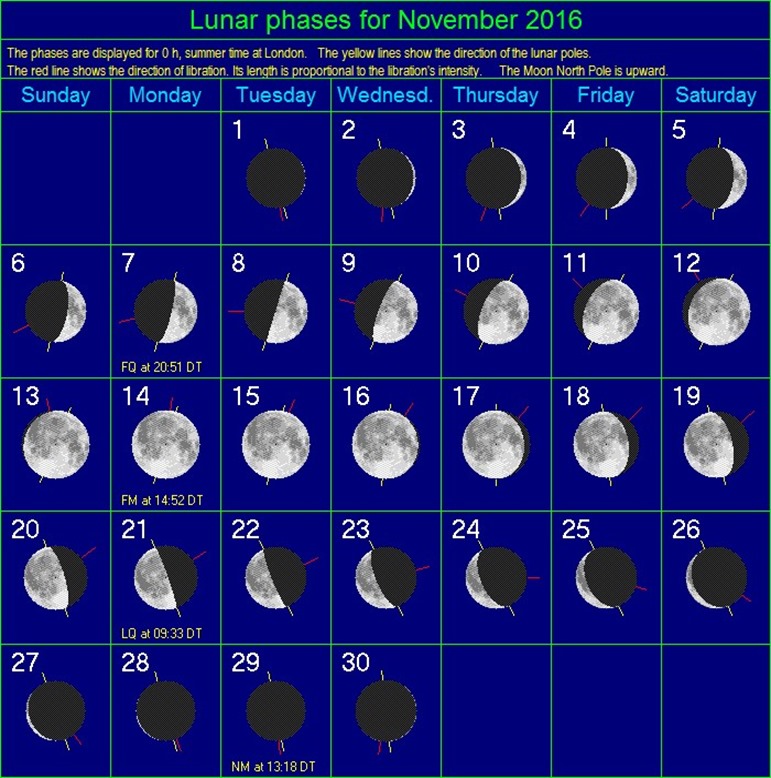

Then, early this year, California Institute of Technology scientists Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown found that the paths of half a dozen extremely distant objects seemed to be similarly tilted relative to the plane of the solar system, and that their perihelia — their closest points to the sun — seemed to cluster together. They estimated that a Planet Nine would weigh about 10 Earth masses and take somewhere from 10,000 to 20,000 years to orbit the sun.

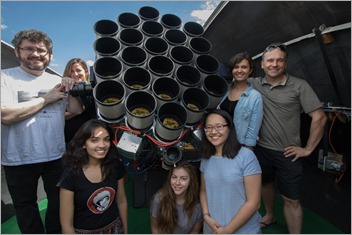

Now, a team led by Renu Malhotra, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, has examined the orbits of four extreme Kuiper belt objects with the longest-known orbital periods and found an elegant relationship among their orbits: They can be described essentially in simple, whole-number ratios. This suggests that they're pulled into these resonances by the gravity from an unseen massive object.

Malhotra was taken aback after discovering the small integer ratios. "It was like, 'Wow, why hasn't somebody else noticed this before?'" she recalled.

Malhotra's team calculated that such a planetoid would be 10 times the mass of Earth and would orbit the sun roughly every 17,000 years — which fits with the Caltech scientists' range estimate of 10,000 to 20,000 years. At its farthest point, this planet would lie a whopping 665 astronomical units from the sun. The results were published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Meanwhile, Brown and Batygin have found more potential evidence of Planet Nine's influence. Their calculations, accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, suggest that the solar system's slight tilt relative to the sun might have been caused by the massive world's pull.

Since the mid-1800s, scientists have wondered why the plane of the solar system — the plane in which all the planets orbit — is tilted 6 degrees relative to the spin axis of the sun, said lead author Elizabeth Bailey, an astronomer and Ph.D. student at Caltech. Given that Planet Nine is suspected to be circling the sun at an even more extreme angle, the scientists calculated that it could indeed have pulled the planets out of alignment with the sun, causing the 6-degree mismatch.

"From our vantage point, it looks like it's the sun that's tilted; but really it's the plane of the planets precessing around the total angular momentum of the solar system, just like a top," she said.

Neither study is a slam-dunk case for the planet's existence, scientists said, but the evidence continues to mount.

The results from both teams were presented at the joint 48th meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society and 11th European Planetary Science Congress in Pasadena.