"We're made of star stuff," astronomer Carl Sagan famously said. Nuclear reactions that happened in ancient stars generated much of the material that makes up our bodies, our planet, and our solar system. When stars explode in violent deaths called supernovae, those newly formed elements escape and spread out in the universe.

"We're made of star stuff," astronomer Carl Sagan famously said. Nuclear reactions that happened in ancient stars generated much of the material that makes up our bodies, our planet, and our solar system. When stars explode in violent deaths called supernovae, those newly formed elements escape and spread out in the universe.

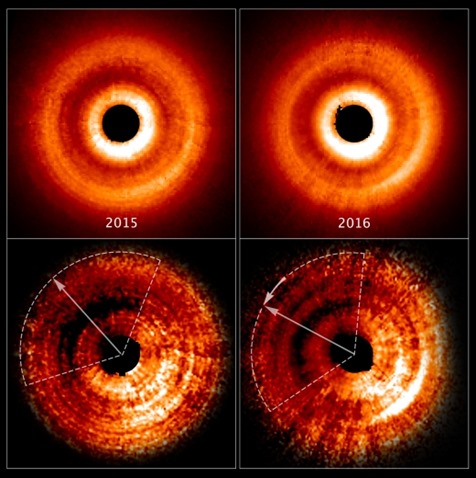

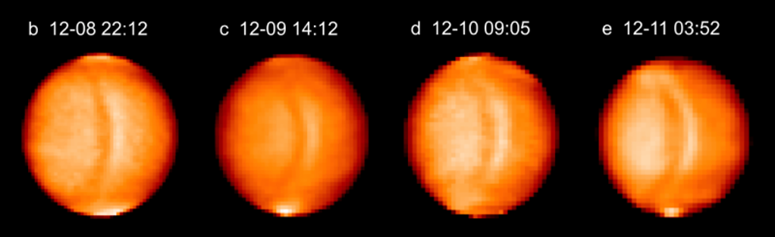

One supernova in particular is challenging astronomers' models of how exploding stars distribute their elements. The supernova SN 2014C dramatically changed in appearance over the course of a year, apparently because it had thrown off a lot of material late in its life. This doesn't fit into any recognized category of how a stellar explosion should happen. To explain it, scientists must reconsider established ideas about how massive stars live out their lives before exploding.

"This 'chameleon supernova' may represent a new mechanism of how massive stars deliver elements created in their cores to the rest of the universe," says Raffaella Margutti, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Margutti led a study about supernova SN 2014C published this week in The Astrophysical Journal. The findings are based on data from NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, or NuSTAR.

"The notion that a star could expel such a huge amount of matter in a short interval is completely new," says Fiona Harrison, NuSTAR principal investigator and Kent and Joyce Kresa Leadership Chair of the Division of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy at Caltech. "It is challenging our fundamental ideas about how massive stars evolve, and eventually explode, distributing the chemical elements necessary for life."

Astronomers classify exploding stars based on whether or not hydrogen is present in the event. While stars begin their lives with hydrogen fusing into helium, large stars nearing a supernova death have run out of hydrogen as fuel. Supernovae in which very little hydrogen is present are called “Type I.” Those that do have an abundance of hydrogen, which are rarer, are called “Type II.”

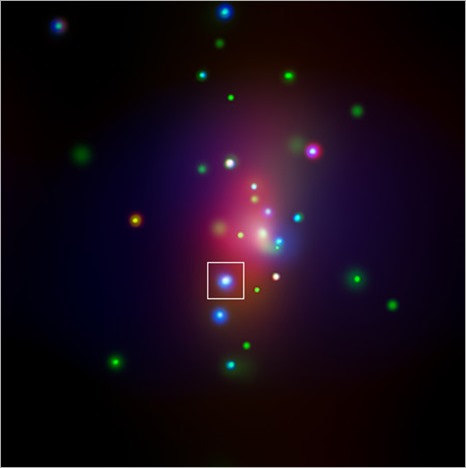

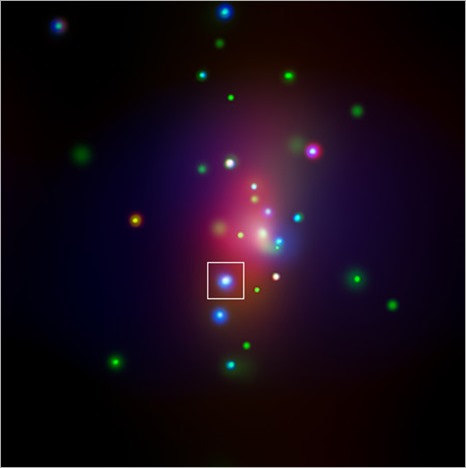

But SN 2014C, discovered in 2014 in a spiral galaxy about 36 million to 46 million light-years away, is different. By looking at it in optical wavelengths with various ground-based telescopes, astronomers concluded that SN 2014C had transformed itself from a Type I to a Type II supernova after its core collapsed, as reported in a 2015 study led by Dan Milisavljevic at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Initial observations did not detect hydrogen, but, after about a year, it was clear that shock waves propagating from the explosion were hitting a shell of hydrogen-dominated material outside the star.

In the new study, NASA’s NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) satellite, with its unique ability to observe radiation in the hard X-ray energy range — the highest-energy X-rays — allowed scientists to watch how the temperature of electrons accelerated by the supernova shock changed over time. They used this measurement to estimate how fast the supernova expanded and how much material is in the external shell.

To create this shell, SN 2014C did something truly mysterious: it threw off a lot of material — mostly hydrogen, but also heavier elements — decades to centuries before exploding. In fact, the star ejected the equivalent of the mass of the sun. Normally, stars do not throw off material so late in their life.

“Expelling this material late in life is likely a way that stars give elements, which they produce during their lifetimes, back to their environment,” said Margutti, a member of Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics.

NASA’s Chandra and Swift observatories were also used to further paint the picture of the evolution of the supernova. The collection of observations showed that, surprisingly, the supernova brightened in X-rays after the initial explosion, demonstrating that there must be a shell of material, previously ejected by the star, that the shock waves had hit.

Challenging existing theories

Why would the star throw off so much hydrogen before exploding? One theory is that there is something missing in our understanding of the nuclear reactions that occur in the cores of massive, supernova-prone stars. Another possibility is that the star did not die alone — a companion star in a binary system may have influenced the life and unusual death of the progenitor of SN 2014C. This second theory fits with the observation that about seven out of 10 massive stars have companions.

The study suggests that astronomers should pay attention to the lives of massive stars in the centuries before they explode. Astronomers will also continue monitoring the aftermath of this perplexing supernova.

“The notion that a star could expel such a huge amount of matter in a short interval is completely new,” said Fiona Harrison, NuSTAR principal investigator based at Caltech in Pasadena. “It is challenging our fundamental ideas about how massive stars evolve, and eventually explode, distributing the chemical elements necessary for life.”

NuSTAR is a Small Explorer mission led by Caltech and managed by JPL for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. NuSTAR was developed in partnership with the Danish Technical University and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). The spacecraft was built by Orbital Sciences Corp., Dulles, Virginia. NuSTAR’s mission operations center is at UC Berkeley, and the official data archive is at NASA’s High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center. ASI provides the mission’s ground station and a mirror archive. JPL is managed by Caltech for NASA.