Venus is often called Earth’s twin, since the second planet from the Sun is only slightly smaller than our own. But its atmosphere is quite different, consisting mainly of carbon dioxide, with a little nitrogen and trace amounts of sulphur dioxide and other gases. It is much thicker than Earth’s, reaching pressures of over 90 times that of Earth at sea level, and incredibly dry, with a relative abundance of water about 100 times lower than in Earth’s gaseous shroud.

In addition, Venus now has a runaway greenhouse effect and a surface temperature high enough to melt lead. Also, unlike our home planet, it has no significant magnetic field of its own.

Scientists think Venus did once host large amounts of water on its surface over 4 billion years ago. But as it heated up, much of this water evaporated into the atmosphere, where it could then be ripped apart by sunlight and subsequently lost to space.

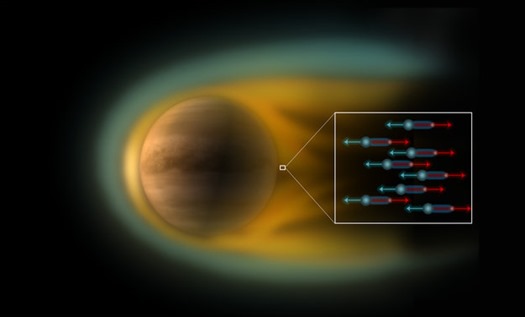

The solar wind – a powerful stream of charged subatomic particles blowing from the Sun – is one of the culprits, stripping hydrogen ions (protons) and oxygen ions from the planet’s atmosphere and so depriving it of the raw materials that make water.

Now, scientists using Venus Express have identified another difference between the two planets: Venus has a substantial electric field, with a potential around 10 V.

This is at least five times larger than expected. Previous observations in search of electric fields at Earth and Mars have failed to make a decisive detection, but they indicate that, if one exists, it is less than 2 V.

“We think that all planets with atmospheres have a weak electric field, but this is the first time we have actually been able to detect one,” says Glyn Collinson from NASA’s Goddard Flight Space Center, lead author of the study.

In any planetary atmosphere, protons and other ions feel a pull from the planet’s gravity. Electrons are much lighter and thus feel a smaller pull – they are able to escape the gravitational tug more easily.

As the negative electrons drift upwards in the atmosphere and away into space, they are nevertheless still connected to the positive protons and ions via the electromagnetic force, and this results in an overall vertical electric field being created above the planet’s atmosphere.

No comments:

Post a Comment